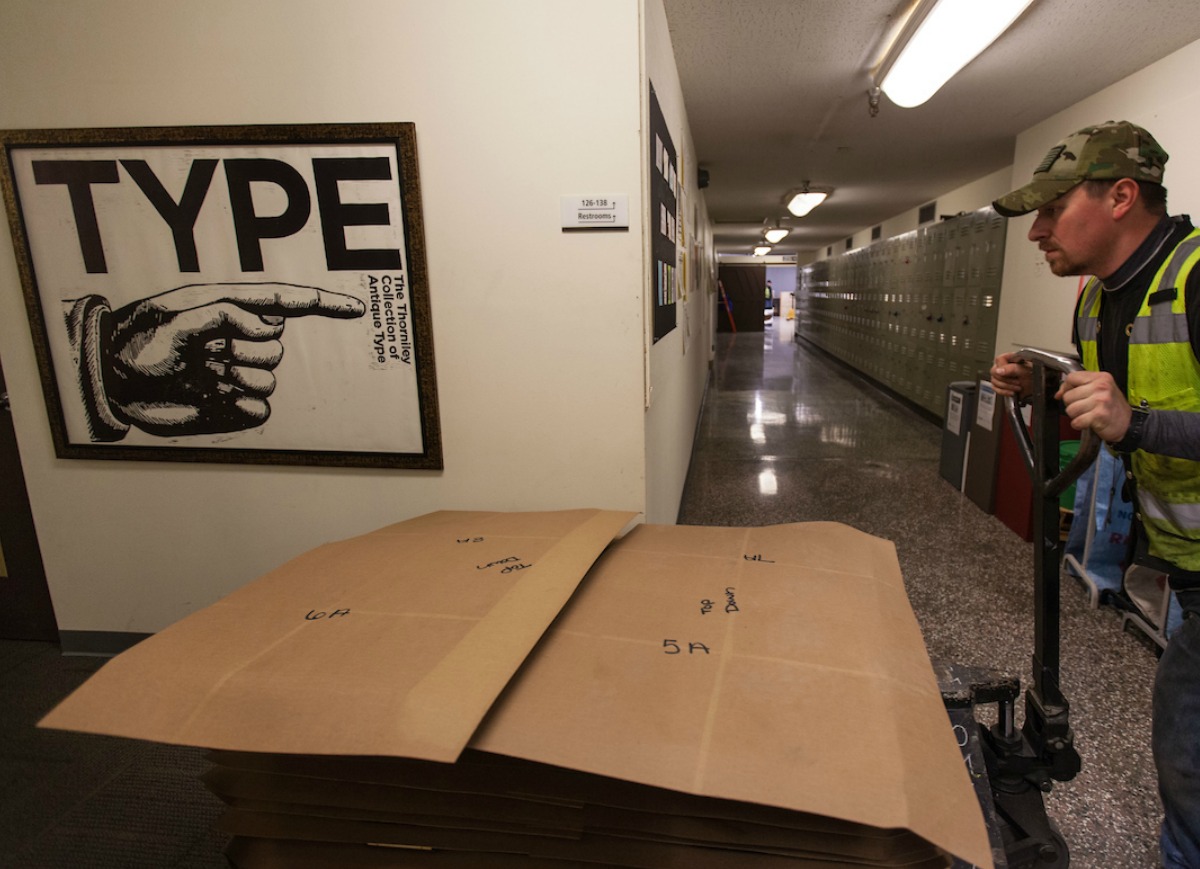

The combined Elliott Press and the Thorniley Collection of Antique Type at PLU now makes up the largest collection of printing equipment in the Pacific Northwest, both in size and variety of type styles and eras represented. Last spring, with the tiniest pica of type to the large, iron 19th century hand press, the Thorniley Collection from WCP Solutions (formerly West Coast Paper) found a new home at PLU, adding more than 1,000 fonts, 40 type cabinets, five presses, antique binding equipment and much more.

“When we began to look for a new home for the collection, we had four objectives in mind: keep it in the Pacific Northwest, keep it intact, preserve it for future generations and place it in the hands of experts who would convert it from a mostly hands-off ‘museum’ into a working and teaching treasure,” said Teresa Russell, chairperson for WCP Solutions. “Happily, PLU enabled us to achieve all four. I am thrilled to be putting the collection in such capable, enthusiastic hands.”

The collection originated with William O. Thorniley, who received a small printing press in 1909 at the age of 10, beginning his fascination with type. He traveled extensively for his job, constantly on the lookout for type. Over time, his collection grew — from discoveries in Alaska and New England, to pre-Civil War type he found in the deep south and Gold Rush-era fonts obtained in California. As Thorniley aged, R.W. (Dick) Abrams, then-chairman of West Coast Paper, offered to buy the collection. Both men desired to keep the collection in the Seattle area. It now serves as an educational resource, honoring local graphic arts and book arts communities.

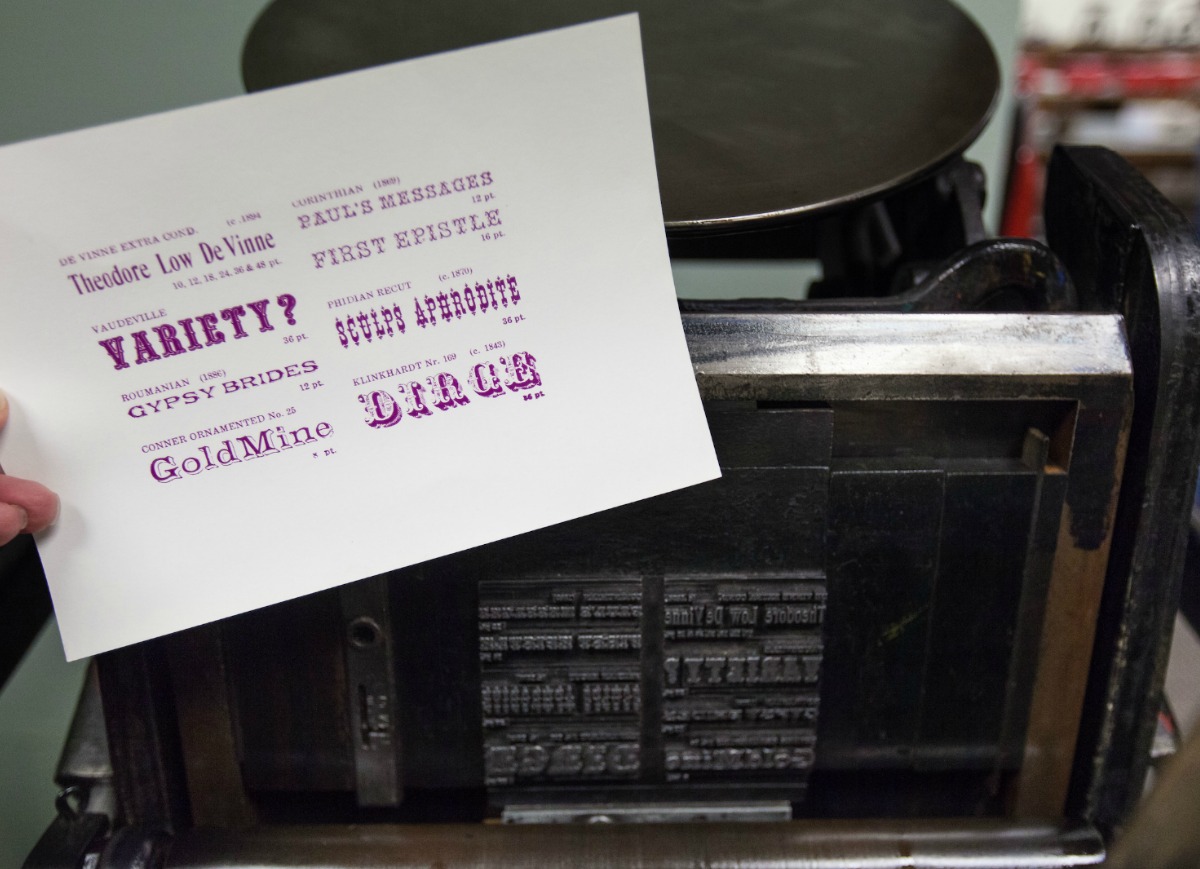

The collection contains fonts that date back more than 100 years, some carved from wood, the rest made of metal. Some of the more notable type includes Union Pearl, which is the oldest, and several fonts of chromatic wood type, intended to print in two and three colors. Much of the type dates to an era referred to as “artistic printing,” which is defined by curves, flourishes, borders and end pieces that were popular in advertising. Many of the rare typefaces also are available in full runs (10-, 12-, 14-, 18-, 24-, 36-point fonts and so on).

Typefaces include those first introduced from 1690 to 1900, making the collection remarkable in breadth. There are examples of type cast at foundries from around the country and abroad (Barnhart Brothers & Spindler, Western, Bruce, Dickinson, Philadelphia, Central, Cleveland, Johnson, as well as Mackellar, Smiths & Jordan). By 1892, about 85 percent of all foundries in the United States had merged into American Type Founders (ATF). It is rare — especially in the U.S. — to see type cast at many of these foundries that were merged into ATF.

Mark Barbour, International Printing Museum director and curator, conducted an appraisal before PLU acquired the collection. He described it as “one of the better 19th and early 20th century collections in the country, showcasing the graphic heritage of the Pacific Northwest to create commercial printing products.”

Another notable item in the collection is the iron Washington Hand Press, produced by Samuel Rust in 1821. It was restored by WCP’s curator, John DeNure, and local letterpress expert and wood engraver, Carl Montford. It was the last style of hand press made in the United States. Another prize of the collection includes a bevy of ornaments and borders used in composition.

The collection features an assortment of “catchwords,” such as “and” or “the” cast on one body — essentially a huge ligature that was often a feature of artistic printing and used in advertising.

Composition tools donated include a “rule bender” — which is used for complex typography — intended to curve decorative rule or leading, allowing for curves, scrolls and scalloped borders.

The collection serves as a resource for students and the community, encouraging interdisciplinary endeavors between faculty authors, visiting artists and scholars.