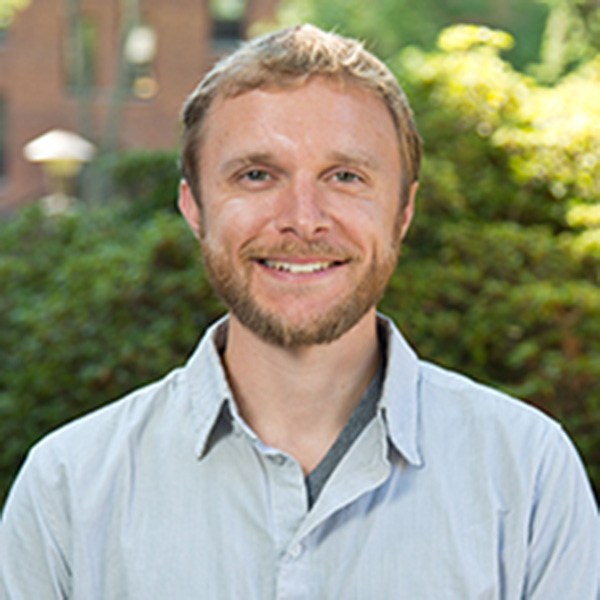

Jacob Taylor-Mosquera ’09

TACOMA, WASH. (Jan. 13, 2017)- Jacob Taylor-Mosquera ’09 was 18 when he returned to Colombia. Although he considered it a homecoming, it took several more visits for him to truly feel at home.

“I grew frustrated because I couldn’t communicate with people,” Taylor-Mosquera recalled. “There was so much I wanted to ask and learn, but I could barely count to 100 in Spanish.”

Taylor-Mosquera was born in Cali, the most populous city in southwest Colombia, but was raised in Gig Harbor, Washington, after being adopted by an American family when he was just a few months old.

Now, after several eye-opening trips back — including one in 2004 when he reconnected with his biological family after a three-month search — he can finally say he feels a sense of belonging there. “This is the first time I’ve truly lived in Colombia,” he said. “I’ve only ever been a tourist before.”

Still, even before he considered Colombia home, it was his family there who motivated him during a turbulent time as a student at Pacific Lutheran University.

Taylor-Mosquera arrived on PLU’s campus, after earning an associate degree from Tacoma Community College, in search of a vocation that would allow him to travel more and collaborate with people from all over the world. But a lack of scholarly direction in the beginning led to academic struggles throughout his first two semesters.

“It got to the point that I was on academic probation for a semester,” he said. “I had to refocus, and did so by thinking about my family in Colombia.”

When he felt unmotivated, Taylor-Mosquera would remind himself of the generational poverty and lack of educational opportunities he’d witnessed during his sojourns back to Colombia. “I would say to myself ‘if they are in the kind of situation they are, and I get to be here, then I really need to get it together.’”

Eventually, an introductory Hispanic literary studies course — taught by Carmiña Palerm, associate professor of Hispanic studies — eliminated his indecision, and Taylor-Mosquera was back on track.

“It was all about Latin American history and had a big focus on political science,” he said. “I loved everything about it.”

Palerm clearly recalls Taylor-Mosquera’s presence in that class and others. “He contributed insightfully to class discussions in the classroom,” she said, “gently pushing his peers to engage difficult conversations about race and class in (Latin American cultures).”

At PLU, Taylor-Mosquera’s passion for travel and cultural inquisition grew. He received a Wang Center grant to conduct research in Ecuador and spent his final semester studying away in Oaxaca, Mexico, where he discovered his knack for conducting research in Spanish-speaking countries.

Taylor-Mosquera earned degrees in Spanish and global studies, building lasting friendships with PLU faculty members along the way. They represented what he aspired to become, he says.

“There were a handful of professors — Carmiña, Michael Zbaraschuk, Tamara Williams, Teresa Ciabattari, Jim Predmore and a few others — who I looked to as people that I wanted to be like,” he said. “They were incredible teachers and mentors, they were presenting at academic conferences, they were traveling all over the world. I saw in them the lifestyle, work and purpose that I wanted for myself.”

And that’s exactly the lifestyle, work and purpose Taylor-Mosquera is pursuing.

His time in Oaxaca inspired the journey he’s on today. “I was working with young people every day, and I felt an unmistakable pull toward teaching,” he said.

Predmore, an associate professor of Spanish who oversaw the capstone paper Taylor-Mosquera wrote in Oaxaca, says “it was one of the best I had seen at PLU.”

After graduating from PLU in December 2009, and spending a year in Panama serving with the Peace Corps, Taylor-Mosquera returned to Tacoma, where he would immerse himself in teaching Spanish.

Serving at Tacoma’s Annie Wright School and SeaTac’s Tyee High School, Taylor-Mosquera relished the opportunity to introduce young people to the language, cultures and peoples of Central and Latin America.

His message to his middle and high school students was simple: “You have one world when you’re monolingual, but when you learn another language you’re opening a door to another world.”

Taylor-Mosquera was inspired by the opportunity to help his students discover a world that he loved. “I saw my students really grow with their Spanish as I had in high school,” he said. “It was a very powerful experience to lead others in that process.”

After three years honing his abilities as an educator, Taylor-Mosquera was hungry to continue his educational journey, and to experience a new part of the world. He enrolled at Leiden University in the Netherlands, completed a research project in Chile and earned a Master of Arts in Latin American studies in 2014.

Taylor-Mosquera now lives with family in Cali, working with adoptees and teaching high school English. He’s savoring the newfound identity he questioned for decades.

“I’ve always felt Colombian in the states,” he said, “but before this I never felt Colombian in Colombia.”

He speaks the language and understands the culture. He built authentic relationships with his family. And he is a newly minted citizen of the country he calls home.

“Becoming a Colombian citizen last April and getting a Colombian ID and passport meant the world to me,” he said, smiling broadly.

Taylor-Mosquera is content in Colombia for now, but he hasn’t lost sight of his vocational goal, the result of the “roadmap to the future” he gained at PLU: “Teaching at the university level,” he said.

Taylor-Mosquera has submitted applications to Ph.D. programs in the United States and Europe. As has been true many times throughout his life, he doesn’t know where he will wind up, but knows where he will always return.

“I have two families, and I have two countries,” he said. “I have no idea where I’ll be next year, in five years or in 10 years, but I know what I’ll be doing, and I know that I’ll always come home.”