Cover Story

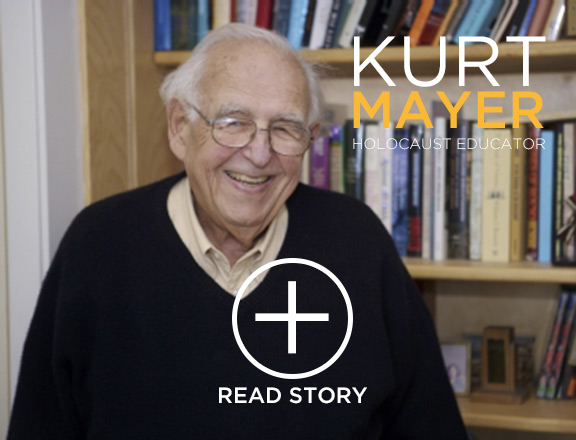

Holocaust Survivor Kurt Mayer’s Family—and the Unexpected Kindness of Strangers—Adds Uniquely Insightful, Emotional Elements to PLU Group’s Study Away Program in Germany

Christensen has led J-Term programs to Germany since 2006. Each year, the students explore many aspects of Germany’s past and present, including Jewish life and the Holocaust, all while staying with host families and speaking lots and lots of German.

As Christensen was planning this year’s program, though, Kurt Mayer came vividly to mind—and suddenly, “host family” took on a much deeper meaning.

Christensen had known Mayer personally—not well, she said, but very meaningfully, through her opportunity to work with him on the German translation of his memoir, My Personal Brush with History.

Christensen ran into Mayer’s son, Joe, at a Powell-Heller Conference for Holocaust Education and asked whether members of his family might be willing to meet with the J-Term travelers before they left. When Joe’s sister, Natalie, a current student at PLU, heard of the program, she said, “We’ll go with you!”

“Suddenly we had the potential for a whole different encounter—for Kurt Mayer’s family to see students engaging with his life and the Holocaust and what he wrote, and for the students to learn more about Kurt through their interactions with his devoted family,” Christensen said.

And so on Jan. 2, Christensen and six PLU students—April Burns ’16, Natalie DeFord ’15, Lexi Jason ’18, Sophia Mahr ’18, Savannah Schneider ’15 and Frances Steelquist ’16—left for Germany. They were met later in the month in Mainz, where Kurt Mayer lived as a child with his parents, by three generations of Mayer’s family: his wife, Pam; his daughter, Natalie; and her son, Elliott. Together they spent a weekend visiting key places from Mayer’s childhood and, at each stop, pausing to read aloud relevant portions of his book.

“There is a 180-degree shift from learning about the Holocaust in a textbook to being in the places where it happened and hearing personal stories of suffering,” Mahr wrote. “I wish from the bottom of my heart that I could have personally met Kurt Mayer. However, meeting his wife, daughter and grandson was wonderful and inspiring. They are continuing his legacy and spreading his story. I did not realize how emotional and moving it would be to meet them and hear this story for myself.”

Here are the students’ reflections on each site, along with Mayer’s original writings that were read there.

MainzSynagogue

“My earliest recollection goes back to age six. My mother took me to my first day in school. We were no longer able to go to public school, so the rooms in the synagogue, which was two blocks from where we lived, were converted into classrooms. Our rabbi was head of the school. There were probably 10 or 12 children in my first- and second- grade classes. I only know of four including myself who survived.”

Christensen said the all-gold interior of the new synagogue is “very edgy and contemporary,” with acoustics so perfect, attendees were enveloped in sound the moment the rabbi began chanting.

“After the service, members of the community invited us to a reception in which Kurt Mayer was honored,” Mahr said. “I met a man, Adam, who was the sweetest. He was so willing to talk about his life experiences with us. When he was younger, he was not as fortunate as the Mayers and was sent to Sachsenhausen. I had never met a survivor of the Holocaust before Adam. The suffering that Adam had to go through because of his blood and beliefs is atrocious. It makes me very angry that anyone could hurt someone as nice as Adam.”

MainzThe Mayer Family’s First Apartment

“At the end of second grade, sometime in late 1937 or early 1938, my dad was suspicious of some kind of government action against Jews. We were living in an apartment house in Mainz and after I had finished the second grade, my folks decided to move to Wiesbaden.”

The next morning, the group visited the site of Mayer’s childhood home, which also was bombed in the war. A new home since has been built there, just a block from the synagogue, with the same house number.

MainzApartment and Butcher Shop Owned by Mayer’s Grandmother

“The evening of my return to Wiesbaden is one of the most memorable of my early childhood. My grandmother talked about having been forced to sell her meat market and house, located at 8 Betzelsgasse, to a Nazi who had secured favorable government financing. My father said we must emigrate but my grandmother said she wanted to die in Germany and my grandfather said he was too old to emigrate. It was a tense time but also a good time. It was one of the few times in my life that I can remember when our entire family was together.”

“(The Mayer) family had owned a butcher shop that was taken over by Nazis,” Mahr said. “I am glad that these Stolpersteine (commemorative brass plaques in the pavement in front of their last address) that are installed in front of the old butcher shop serve as remembrance of their lives.”

WiesbadenHiding Place of Mayer’s Father

“My father returned to Wiesbaden from Frankfurt since it was evident he could not hide with his cousins, but my Mom told him he could not stay because the Gestapo was looking for him. We had no Christian friends in Wiesbaden since we had not lived there very long, and in any event, people were afraid to harbor Jews because it would have been like harboring a criminal. An elderly couple named Bach owned a delicatessen. Their business and apartment were two doors up the street from Taunus Strasse 23, our rented flat. Mr. Bach had been an officer in World War I. Mrs. Bach told my Dad that she would hide him in the cellar, and although food was rationed, he would have plenty to eat and my mother could come to the store and get verbal signals on any changes in conditions. So my Dad went into hiding in the basement of the deli.”

The group observed and took a few pictures of the house from the outside, Christensen said, and certainly didn’t expect any interior access. But a woman who lived in the building and who arrived home just as the group was gathered agreed not only to invite everyone in, but also to open the cellar where Kurt Mayer’s father had hidden to escape the SS. Although she had lived there for many years, the woman said she had no idea a Jew had ever hidden there.

“It was really moving to see the living conditions of the cellar. It was all exposed brick with lots of cobwebs. It was drafty, and the floor was dirt and uneven. But for Kurt’s father, this cold, lonely cellar was a haven,” Jason said.

Christensen said the cellar probably looks the same today as it did then—dark, dungeon-like and bare. .

“… It was uncomfortable to put myself in his position,” Jason said. “This cellar was pretty gross, but it was nothing compared to the horrors of a camp. Realizing the sacrifices that Jews (and other persecuted people) had to make in order to stay alive is always a reality check for me. Knowing that hiding in this cellar and getting a little food and human contact once a day was how Kurt’s father and many others lived is hard to stomach. It’s difficult to imagine now, but it was a reality for them.”

Bad NauheimJewish Boarding School

“At about 6.30 a.m. the morning of November 9, 1938, I was on the top floor of the boarding school in Bad Nauheim. As we were about to get up, we heard a lot of noise and we were told to go out on the street. We packed some clothes in suitcases, but we still had our nightshirts on and no shoes. It was cold and we were marched barefoot in a line of two or three by civilians with revolvers exposed and pointing at us. Cars driving adjacent to the sidewalk accompanied us for about one mile to the police station.

“We were held in the outside yard for several hours and I developed frostbite on my toes. Our male teachers were gone. That night we learned they had been taken to concentration camps. After what seemed an eternity, we children went back to the boarding school by ourselves. When we got back, the same men who had taken us to the police station were there and herded us around the schoolyard. We watched from the perimeter of the schoolyard as these same men gathered the prayer books and the Torah, poured gasoline on them and burned them in the center of the schoolyard. All the kids were confused and crying.”

Christensen said it took a bit of work to reach someone who could let them into the school, in part because its name had changed since Kurt Mayer’s day. It is now aptly named for Sophie Scholl, a courageous young resistor who lost her life for spreading anti-Nazi propaganda. But Patricia Koch, the administrator of Sophie-Scholl-Schule Wetterau, agreed to meet the group—even on a Saturday.

“I look back at that Saturday in January full of thanks that I was able to share in the story of the Mayer family and to get to know so many good, warm, open people,” Koch wrote to Christensen after the trip. “I was … profoundly moved to be able to be part this gathering.”

After gathering first on the school grounds near a small memorial for schoolchildren killed in the Holocaust, everyone went inside: first to the ground floor, where nursery-rhyme paintings from Kurt Mayer’s day still adorn the walls. They then went to the top floor, where Mayer and the other children had slept.

“This point, for me, was the most emotional,” DeFord said. “The point when I learned a story of a very young girl (I think about 3 years old) [the daughter of the school’s director] who died because she had swallowed a barrette and not a single [doctor in town] would help her because she was Jewish.”

The school was especially emotional for the Mayer family, Schneider said, because they were able to see where Kurt Mayer had slept and what it had looked like, and better understand what he had experienced.

“At the school, Mrs. Mayer said that the book reading at the places was important because, ‘It helps us to imagine,’” Schneider said. “It was one thing to read and study and watch movies on history and to be in the place of that history. There is a different, more one-on-one personal element to reading, but there is an experiential element that can only be remembered at the place and vice versa. However, there is also the truth of never being able to actually remember something that is not ours to remember–not being able to experience what has already happened.

“That is why this stood out as so special to me that Mrs. Mayer said that. I don’t need to remember to begin to understand—I just need to be able to imagine.”