Pave the Way

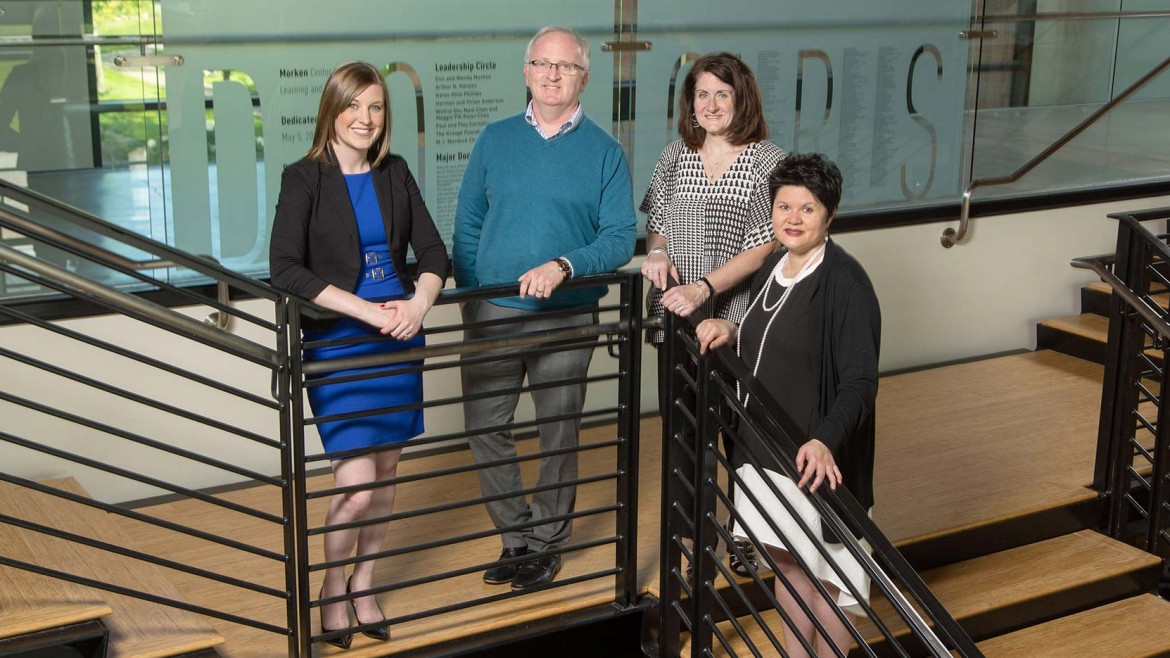

Maria Chávez leads with her own experience when she addresses academic opportunity and achievement. Specifically, she empathizes with students who come from marginalized populations.

Chávez, chair of politics and government and associate professor of political science, identifies as Latina. She’s a native Spanish speaker who didn’t learn English before beginning school. She was raised in an immigrant household in the Southwest and experienced many of the obstacles fellow Latinos face every day in the U.S.

Like many who come from a similar background, Chávez was the first in her family to graduate from college, despite the barriers she faced. She came from a home and a school system that didn’t encourage her to pursue higher education. She didn’t know the questions to ask regarding that pursuit.

“It informs the research I do,” she said.

And in the fall, Chávez’s past struggles and successes informed her talk at the annual Pave the Way Conference, where she served as one of three featured speakers. She presented to hundreds of educators, policymakers, and nonprofit and industry partners about the opportunity gap in Washington state. The annual conference focuses on increasing educational attainment by supporting historically marginalized, underrepresented and underserved students across the lifespan of learning.

The theme for the fall event, which took place Oct. 19 at Central Washington University, was “Advancing Equity, Expanding Opportunity, Increasing Attainment.” Participants shared effective strategies for educational success among underserved populations of students, engaged lifelong learning partners through meaningful professional development, and fostered cross-sector collaboration on issues related to student access and readiness.

“It’s important that, if we want a strong democracy, we must have inclusion from all voices,” Chávez said. Inclusion of all voices is paramount to educational success for all students, marginalized or otherwise, she added. “The more connected we are, the better able we are to improve society. Diversity in profession and education benefits everyone.”

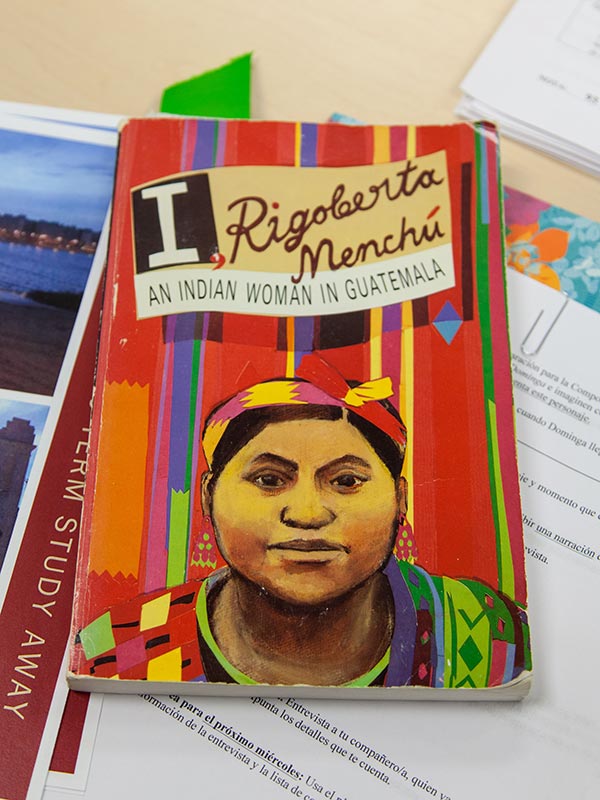

Chávez said her speech at the conference focused on the findings of her most recent book project, which is due out in 2019. The book, titled Latino Professional Success in America: Public Policies, People, and Perseverance, explores how first-generation Latinos became professionals, their experiences as professionals amid the country’s institutional racism, and the policies and programs this group believes would help increase their presence in the professional world.

Chávez says Latinos are the largest ethnic group in the U.S., yet they significantly lack representation in professions across the board.

“Latinos are underrepresented in powerful segments of American society,” she said. “We must ask what the implications of this continued political and professional underrepresentation is on our society and our democratic institutions. Beyond issues of representation, this research is important for our civic health.”

She said that fact clearly illustrates the need to address the achievement gap through better public policies and educational support systems at every stage in the pipeline.

“It’s inequitable practices in education that lead to a lack of achievement for groups of people,” she said. “If we can’t fulfill our potential because we just don’t have a way to do it, then we aren’t getting to the realization of human dignity.”

Underrepresentation by the numbers

Maria Chavez cited U.S. Census data that show Latinos represent 17 percent of the population at 55.4 million people. It’s estimated that representation is going to grow significantly in the next several decades. She noted that Latinos and other people of color are expected to account for 56 percent of the population by 2060. Despite these numbers, representation of the Latino population still significantly lags:

Nation's Lawyers

Scientists and engineers

Practicing medical doctors

Full-time faculty members at degree-granting institutions of higher education

Nation’s Congressional representatives

Elected officials nationwide

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, American Bar Association, National Science Foundation, American Medical Association, National Center for Education Statistics, National Association of Latino Elected Officials

Chávez said she sought out and received support throughout her own educational journey, despite external challenges: a cultural background in which she says women’s ambitions were often suppressed and a racially segregated community in which Latinos were often oppressed. She started in community college, transferred to California State University, Chico, and eventually earned her master’s degree there. She made the dean’s list each semester and was encouraged to apply to graduate school, landing her at Washington State University where she earned her Ph.D. She’s been teaching classes at PLU since 2006.

The key to persistence for marginalized students, and subsequently their success, is building support systems similar to the ones she had, Chávez said. To get there, she says leaders should avoid polarizing, zero-sum approaches to solutions and exhibit compassion for all sides.

“It’s really about getting us together and making this society better,” she said. “These conversations have to happen. But they have to happen better, more thoughtfully.”