Exploring Egyptian tombs

The moment before the chamber door of an ancient tomb cracks open, a sensation of excitement, of discovery is running through Don Ryan ’79 – renowned archeologist and Egyptologist and PLU faculty fellow.

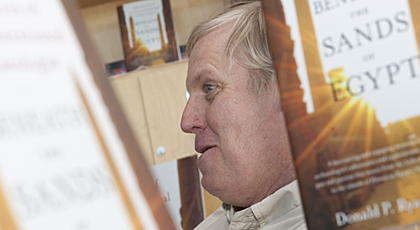

PLU Faculty Fellow Don Ryan knows a thing or two about Egyptology. After all his team did rediscover Hatshepsut.

This moment of exhilaration may come from months, if not years of research – meticulous and sometimes thankless research.

“First I do my homework,” Ryan said. “The fieldwork in some ways is the tip of the pyramid. No pun intended.”

But what is born from the shelves, books and transcripts of the library can really take on a life of its own in the field. Ryan highlights his adventures throughout the years in his most recent book “Beneath the Sands of Egypt – Adventures of an Unconventional Archeologists.”

In much of the book, he talks about his work in Egypt, where his team discovered the mummy of the famous female pharaoh Hatshepsut, who ruled from around 1502 to 1482 B.C.

Since the original dig in 1989, he has returned several times to continue the PLU Valley of the Kings Project.

Ryan will speak about the most recent discoveries during a talk this week at the Scandinavian Cultural Center in the UC from 7 to 9 p.m. on Wed., Sept. 29. Lawrence M. Berman from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston will also be there to describe the contents of another tomb discovered in 1915 in middle Egypt.

The Valley of the Kings Project is a tale of rediscovery that continues to this day.

In 1903, Howard Carter – famous for finding Tutankhamen’s tomb in the 1920s – found the royal tomb and it was designated K60. In the burial chamber, a coffined mummy and one on the floor were found. The coffined mummy was removed and sent to Cairo. The chamber was then sealed and its exact location lost for nearly 80 years.

Then in 1989, Ryan and his team found the tomb’s entrance using only a broom – on the first day of digging no less. Ryan had done his homework and had approximated its location from Carter’s notes.

“People think I have a special touch for finding things,” he said. “I’d say it’s more of doing one’s homework than anything else.”

In the tomb, burial remnants were found along with the second mummy, still lying on the floor. The quality of the mummy was striking a royal pose: left arm bent at the elbow diagonally, the left fist clenched and the right arm straight along her side. The pose and the quality of the mummification suggested royalty, Ryan said.

It wasn’t until the spring of 2008 that the mummy was removed and shipped to Cairo to be examined. It was one of four candidates that the Egyptian authorities suspected could be Hatshepsut.

By a stroke of luck, Egyptian scientists discovered a molar inside a canopic box that bore the royal names of Hatshepsut. The tooth matched within a fraction of a millimeter the space of a missing molar in the mouth of Ryan’s 3,000-year-old mummy.

“Like Cinderella’s slipper,” he said.

And discovery continues with more visits to the site and more examination of The Valley of the Kings.

“The things that have survived are pretty amazing,” Ryan said. “To understand where we are today, you have to understand where we’ve been. The truth is the world did not begin when you were born.”

What has been found in Egypt continues to amaze and challenge today’s scholars to think about the past, he said.

“These guys (ancient Egyptians) are thinking about some of the same issues we are today,” Ryan said. “It let’s you know people have always been smart. We’re not any smarter just because we have laptops and iPhones.”

Material from a 2008 Scene article was used in this report.