Another Historic Harstad Hike

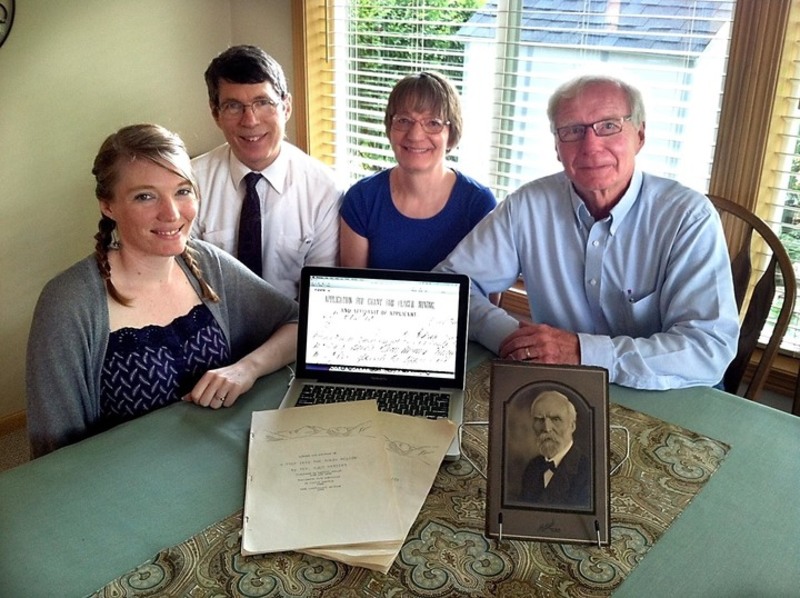

From left, Carol Yenish of Mankato, Minn., the Beckers’ daughter and great-great-grandchild of PLU founder Bjug Harstad; Vance and Linda (Harstad) Becker of North Mankato; and Mark Harstad of Mankato display electronic and typed records of their ancestor’s journey to Yukon Territory in search of gold. (Photo: Amanda Dyslin/courtesy of The Free Press of Mankato)

Founder’s descendants retrace 1898 Gold Rush quest to save PLU

In 1898, Pacific Lutheran Academy was in serious trouble. Following the financial crisis known as the panic of 1893, the economy had crumbled, and unemployment had soared. Contributions to the new school had fallen off considerably, and debt from its first building (considered rather extravagant by some) seemed insurmountable.

PLA, in other words, needed to strike gold. Perhaps literally.

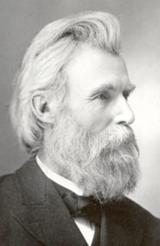

Concluding that extraordinary times did indeed call for extraordinary measures, the Rev. Bjug Harstad – the Norwegian immigrant who  founded Pacific Lutheran University in 1890—joined the Gold Rush in hopes of saving his school.

founded Pacific Lutheran University in 1890—joined the Gold Rush in hopes of saving his school.

Harstad’s efforts were valiant, if not triumphant—and now, his descendants are retracing his steps in commemoration.

On July 25, three generations of Harstads plan to backpack the rugged Chilkoot Trail from Dyea, Alaska, to the headwaters of the Yukon River in Canada.

“There’s always been this powerful historical consciousness,” Mark Harstad, Bjug Harstad’s grandson, told his hometown paper, The Free Press of Mankato, Minn. “This is just a part of the fabric of who we are.”

In total, nine members of Harstad’s family will hike 33 miles over four and a half days, said Carolyn Harstad, 77, the wife of Peter Harstad, from Lakeville, Minn.: “Eight miles one day, four another and so on.”

The hikers and other Harstad family members will converge in Skagway, Alaska, on July 23, she said. Then, after taking in a mandatory trail orientation, a family hike and a play, the group will shuttle to the Dyea (pronounced DIE-ee) trailhead for a rise-and-shine 7 a.m. departure July 25. And they’ll have historic PLU memorabilia with them: University Archivist Kerstin Ringdahl said one of Bjug Harstad’s granddaughters stopped by recently to get a photo of the mukluks Harstad wore in Alaska.

“Our family group of 15 ranges in age from 24 to 78 and is made up of a number of writers, historians and educators,” Carolyn Harstad said. “All 15 have college degrees, and there are several with M.A. and Ph.D. degrees. I think Bjug would be proud of his offspring.”

Bjug Harstad’s trip likely was a little more arduous than his descendants’. Then 50 years old, Harstad traveled on the S.S. City of Seattle steamer from Tacoma to Skagway, and then on a large flat-bottomed barge for the remaining 100 miles to Dyea. From there he trudged over the famously grueling 3,500-foot Chilkoot Pass to the headwaters of the Yukon River, transporting, literally, a ton of goods on a sled. From there Harstad took handmade boats and rafts down the Yukon River to the boomtown of Dawson City in Yukon Territory, where gold had been discovered in 1896.

Harstad had high hopes—grounded in solid faith—for his mission. In a letter home dated April 17, 1898, he wrote:

“Many are surprised that the undersigned should go to Alaska among gold seekers. I should like to ask those if they know anyone who has a better reason for going into the gold fields than I. … It is firmly impressed both upon me and many others that our school on the Coast is responsible for large sums of borrowed money that must be repaid. We are in duty bound to try every reasonable means of fulfilling our obligations. Perhaps it is the Lord’s will to unlock for us some of the earthly treasures that are deposited here.”

Harstad returned penniless—and decidedly goldless—18 months later, having traversed the entire Yukon River. (The economy eventually righted itself, as did PLU.)

But Harstad didn’t come back to PLU completely empty-handed: He lugged back the massive moose rack that hangs today in the office of Alumni & Constituent Relations.

And, of course, that first, possibly extravagant building still stands at PLU, too—now called Harstad Hall.