PLU French professor Rebecca Wilkin wins the 2024 Translation Prize

Image: PLU Professor of French Rebecca Wilkin teaching a course titled “French / Francophone Feminisms.” (Photo by Sy Bean/PLU)

By Zach Powers

PLU Marketing & Communications

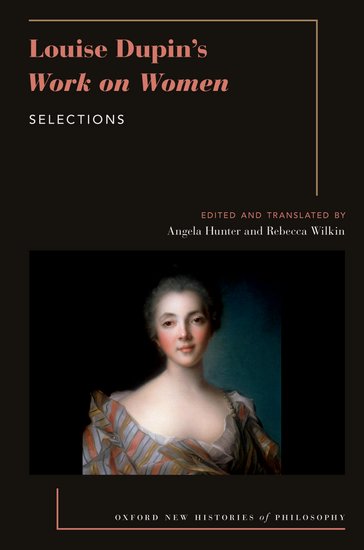

The French-American Foundation has announced that PLU Professor of French Rebecca Wilkin is one of the winners of the 2024 Translation Prize. Wilkin and her co-editor and translator Angela Hunter, an English professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, received the nonfiction prize for their translation of the eighteenth-century text “Work on Women” by Louise Dupin (also known as Madame Dupin).

Wilkin teaches in multiple academic programs at PLU, including French & Francophone Studies, Global Studies, the International Honors program, and the First Year Experience Program. She is the author of Women, Imagination, and the Search for Truth in Early Modern France (Ashgate 2008) and of many articles on Descartes and Cartesianism, early modern women philosophers, and early modern feminist thought. She also is the co-editor and translator of a collection of translated selections from the work of Gabrielle Suchon published by the University of Chicago Press in 2011.

PLU News recently caught up with Wilkin to discuss her award-winning book.

Why was it meaningful to be recognized with this award, in particular?

It is such an honor to receive this prize because there are so few literary honors that recognize the discernment and labor involved in translation. A good translation is invisible, and so translation tends to be an invisible, underappreciated art. Receiving this prize was also very unexpected.

Unexpected? Why is that?

We never thought of our edition of Dupin’s Work on Women primarily as a translation. The translating we did was just one part –by far the funnest part!– of the project.

Oh that’s interesting. Can you share a bit about your process putting this book together?

First, we had to locate manuscripts that had been broken up and sold at auction to various archives in the 1950s, then we had to decipher and transcribe them, then we had to figure out Dupin’s intentions for the shape of her work, because she never actually finished it– her Work on Women was a work in progress! And once we had the text established and translated, it took us an incredibly miserable year to track down Dupin’s references to over 200 sources. And my brain still hasn’t recovered from cranking out five introductions (one for each part of the Work) in the space of three months; we knew these would be crucial for allowing readers to understand Dupin’s context and appreciate her claims.

Wow, that is a lot of work!

Yeah, and clearly, the jurors who selected our book for the 2024 French-American Foundation Translation Prize took a broad view of translation. They embraced all of the labor that went into making Dupin’s Work on Women accessible to English speakers, and we are so moved by this recognition.

What’s the origin story of this book?

At first, I had no intention of editing – much less translating – Dupin’s work. At first, I just wanted to write an article about Dupin with PLU French and Global Studies major Sonja Ruud ‘12, who had held a Kelmer-Roe Student-Faculty Research Fellowship with me. The catch, though, was that we couldn’t write an article about a text that didn’t exist! So we started collecting and transcribing pieces of it just to have something to read and work with. Terrifyingly (because of the magnitude of the project, which I barely even grasped then), it began to dawn on me that editing Dupin would be a huge service to other scholars and potentially the most important contribution of my scholarly career.

When did Angela Hunter, your co-author and translator, get involved?

In 2016, I reached out to Angela, the only other American scholar working on Dupin. We talked on the phone and a few months later, though I had never met her in person, I flew to Little Rock. We spent a week at her dining room table hashing out a book proposal.

When you look back on it now, what do you think inspired you to grow this research and translation topic that began with your former student, and graduate it into this larger book project?

In retrospect, three things inspired me to undertake this project–what we now refer to as “feminist recovery work.” First, the intellectual importance of Dupin’s Work on Women. It’s notable that Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the famous political philosopher, had been Dupin’s secretary for this project, that most of the manuscripts are in his handwriting, and that we can trace some of his most original ideas to her.

Second, the clear need for access to the text. People knew of the existence of the Work on Women after it was auctioned off in the 1950s, but it was largely neglected, and one very obvious reason for that neglect is that it was a work by a woman about women. You could say that the tides have turned. There is now pent-up demand for the work of women philosophers from this time period, whether for scholarship or for syllabi. It was the perfect time to finally bring Dupin to the public.

Third and finally, the possibility of collaborating with Angela, without whose smarts and stamina none of this would have seen the light of day. I deeply cherish the friendship that has grown out of our intense collaboration. It has been the highlight of my scholarly career.