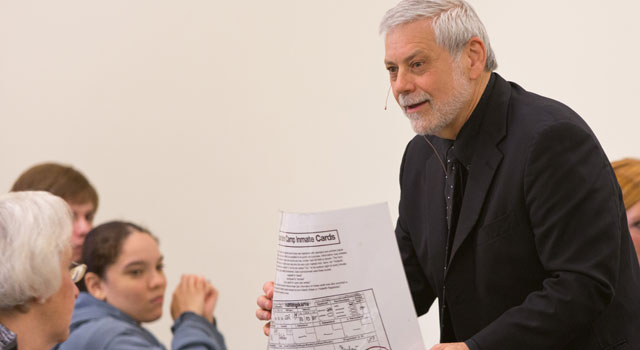

Edwin Black, author of “IBM and the Holocaust” speaks at a Brown Bag Lecture as part of the Kurt Mayer Chair in Holocaust Studies program at PLU on Tuesday, Oct. 16, 2012. (Photo by John Froschauer)

Journalist and author examines IBM’s role in the Holocaust

Let’s make one thing clear, said Edwin Black, an investigative journalist and author of “IBM and the Holocaust.”

“There would have been a Holocaust without IBM,” he told a group of about 100 people who came to listen to him talk about the years of research, and hundreds of archives searched for his book. “But it would not have the industrial, automated Holocaust,” where each camp had a number, each victim had a tattoo and each victim was researched back through the generations.

Black talk was part of the Fall Lecture series under the Kurt Mayer Chair in Holocaust Studies programs. The second lecture will be Nov. 15, when Peter Altmann will present a special viewing of “Adele’s Wish,” which tells the story of Altmann’s mother, Maria, and her efforts to retrieve the family paintings taken during the Holocaust.

During his one-hour lecture, Black presented document after document, found in archives, IBM files and, in one case, a rabbi’s closet, that show that IBM’s eager complicity in the Holocaust began in the early 1930s and didn’t end until the final days of the war, when the company deftly buried the entire matter in forgotten archives. If IBM had any squeamishness or second thoughts about the Nazis’ agenda, “all they had to do was stop producing the punch cards and it would have been like a rifle without bullets,” Black said of the Reich’s mass transportation and cataloguing program in the camps.

But the company didn’t stop until the final days of the war in 1945, he said.

For the next 60 years, IBM’s creation of the Hollerith punch-card system was largely forgotten, until in the mid-1990s, Black spotted one of the machines in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum. He became curious, and he, along with 100s of volunteers, began to dig. He discovered that IBM created this punch-card machine specifically for the Third Reich, and the new technology not only allowed the Nazis to correlate information from birth, medical, financial and work records, but track down and identify Jews and others targeted for the campus, before the tanks even rolled into the towns and cities across Europe.

“They engineered a custom program,” he said. “The Nazis wanted an alphabetized list when they rolled into town,” to round up the Jewish population.

Since the book was first published in 2001, IBM has been largely silent on his research, Black said. And holding up a series of laminated photocopies, which showed documents and punch cards, all bearing the IBM logo, name or signatures, Black explained that the company really didn’t have a defense against such damning evidence.

“This is why your president won’t be getting a call from IBM tomorrow,” Black said, pointing to document after document.

In large part, Black said, IBM tried avoid any sort of paperwork related to the camps, but the Nazis were meticulous record keepers and kept thousands of documents related to the project. Black and his researchers had requested that IBM release these and other documents in the company’s archives. The company refused. But IBM officials did agree to release the documents to a professor-rabbi at New York University, who was studying the Dead Sea scrolls. But IBM’s effort to bury the evidence once again, failed.

“There were six boxes in his closet,” he said. “He at first said he wouldn’t give them to us, and then announced he was taking a long lunch.” And left.

Some of the most damning finds were in those boxes, including company phone books that included numbers to contact the IBM office in the camps.

And as to IBM during the war? The company simply provided information to both sides – such as creating the weather reports for both the Allied troops and the German troops on D-Day in 1941. The motivation of company officials, including IBM’s president Thomas Watson, was not so much ideology, as money.

“It was a business decision,” he said.