Art and Anthropology Faculty Join Forces for Important Historical Illustrations

Q&A With Professor Michael Stasinos and Associate Professor Bradford Andrews

TACOMA, WA (Jan. 16, 2015)—In a groundbreaking merger of art and anthropology, Pacific Lutheran University Art Professor Michael Stasinos has been developing important historical illustrations in collaboration with PLU Associate Professor of Anthropology Bradford Andrews.

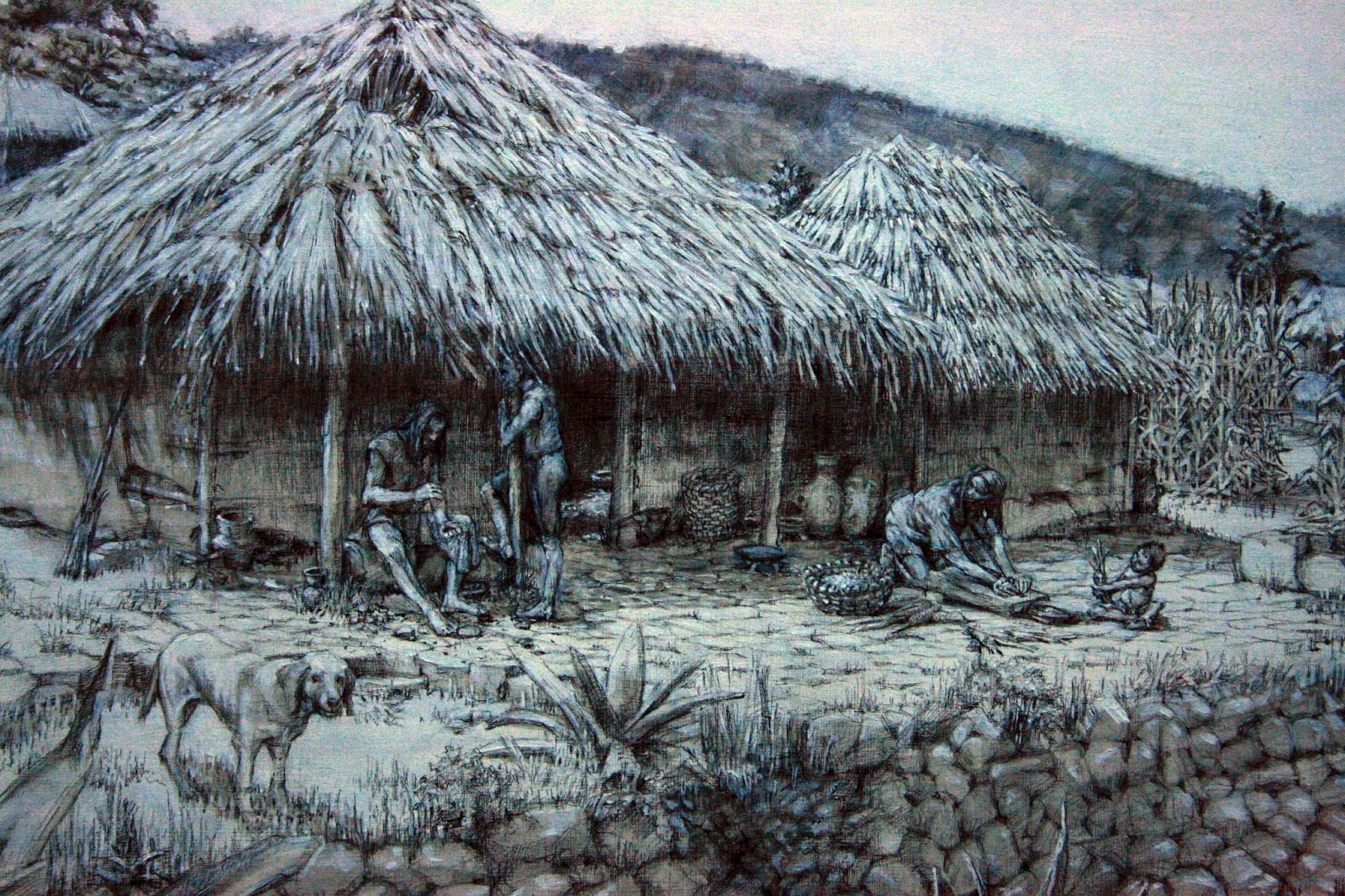

One of those is an invaluable painting illustration that artistically has brought to life a market scene in the city of Calixtlahuaca, an important archaeological site for studying Mesoamerican urbanism in the Postclassic period (A.D. 1100-1520). Research at this archeology site has been conducted by the Calixtlahuaca Archaeological Project—supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and sponsored by Arizona State University—in which Andrews has been actively involved.

Upon completion of a series of illustrations for this project, Stasinos and Andrews discussed this unique collaboration of art and archeology.

Q: Professor Stasinos, tell me a little bit about your art background and how you and Professor Andrews got connected with each other.

Stasinos: I graduated from the New York Academy of the Figure of Art. I was interested in the figure and learning about historical and traditional painting techniques. I was there more with a “fine arts” sort of an agenda. I originally arrived at PLU as an adjunct faculty covering for the professor who was teaching here. Then eventually I became a visiting professor, and I was lucky enough that the department liked what I was doing. What I brought to the table was the traditional training. One of the classes I teach here at PLU is Figure Drawing. So this is kind of where the connection with Professor Andrews came in, because he wanted someone that would bring the scientific information of the archaeological site to life with living people interacting in that space.

Andrews: I came to PLU the same time when Stasinos got his tenure-track position, and that’s when we met. But I did not contact him until I met one of his students who was swiping people in at the front desk of the Names Fitness Center. The day I noticed she was drawing her hands, I asked who her professor was, and that is how I connected with Stasinos. I had been thinking for a while that I wanted to find somebody who would be interested in illustrations based on archaeological interpretations. I have always been very intrigued by that kind of thing because a picture like that is worth a thousand words. Hence, I saw that as an opportunity, and we got together.

Q: Can both of you share how the collaboration of creating the market scene occurred?

Stasinos: While Professor Andrews was looking for someone to do the illustrations, I saw that as an opportunity for an assignment in my class. Because we would be drawing for an archaeological project, students not only have to do research and preliminary studies; they also have to communicate with someone else at stages of its development to show the progress and get feedback and make changes based upon that feedback. I saw it as a great opportunity for students to experience. Instead of having one student doing something for him, I tried to give students the opportunity to build something over time.

Andrews: My specialty is stone-tool analysis, so I have evidence that in the city people in most of the households were actually making their own tools. At first I wanted to get a scene of somebody flaking stone to make tools, so that’s what I got (see below).

Stasinos: He came in the first day of the class, and he actually demonstrated making an arrowhead in front of my class. While he was doing that, I took photos and posted them on Sakai for the students to access later, so that they can draw out the scene based on the pictures I took. The guy in there (below) doesn’t look like Bradford. He’s got long hair on and clothing he wasn’t wearing, but it is from a photo of him flint-knapping in class (laughs).

Andrews: After this was done, I talked to the project director, my colleague at Arizona State University. I asked him if he would like a sitewide reconstruction. And so that’s when I talked to Stasinos about the market scene.

Stasinos: We did the assignments in this class two years in a row, while the class only ran once a year. At the end of doing the kind of the combination assignments together to do these illustrations, we have realized that from what Andrews was seeking, he would really need someone who would commit to doing it over a year or two outside of class.

So what ended up being the product was out of this classroom experience with the students. Michael Smith from Arizona and Bradford approached me to do the market scene.

Q: Professor Stasinos, what was the painting process like?

Stasinos: The background of the illustration of the market scene was self-made in a way. If you look at the original photo (below right) I was initially provided, there isn’t a house on it. But there is evidence that the temple structures existed there. Also in the original picture, the foreground is filled with plants and corn. So a lot of the painting process was really how you activate that foreground.

The first thing I worked on was the background, but it ended up being the first and last thing I did because every time I presented it for feedback, there is going to be a little bit more of the houses needed. Even later, when I got it to where it was acceptable, the last thing I had to make changes to was their road system on the hill, and also their watering system and drainage. When you see the dark lines on the hill, there are certain directions that they were supposed to go toward, so I had to change when the directions I had on there were not correct.

After I had the background painted, I laid a plastic over the top of the actual painting. I drew on the plastic, and if the figure didn’t work at one place, I erased it out and rearrange and such. When it was finally ready, I would then transfer it onto the actual painting (see image at left).

At the very last stage, I used Photoshop for minor retouches. In early time, for instance, if the sky on the painting was not bright enough, the painter would have to go back and physically paint the sky brighter. So now with the help of modern technology, I could use Photoshop for more of the retouching adjustments like that. For example, in one of my early paintings done for Bradford, my last feedback on it from Bradford was no ancient people would ever lay down their bows on the ground because they wouldn’t want them to get wet, so then I took the other references and I drew them and Photoshopped the painting so that in the very last version, the bows appeared to be leaning against the wall (below).

Usually the finished version would only be a digital copy as an illustration. But if it was for the museum, I would have to repaint. For this market scene of the city of Calixtlahuaca, I have provided three to four versions in which I had done some minor color adjustments to the sky and the foreground for them to choose which to be the final illustration.

Usually the finished version would only be a digital copy as an illustration. But if it was for the museum, I would have to repaint. For this market scene of the city of Calixtlahuaca, I have provided three to four versions in which I had done some minor color adjustments to the sky and the foreground for them to choose which to be the final illustration.

A lot of people commented on the complexity of this product. But at the beginning stage, there were just about 15 figures. The earlier version of the painting was a very simplified version, and once I figured out the composition, I would add more onto the first layer to make it more complex.

Compositionally, what I was trying to do as an artist is to put order into the chaos. In the end I had to edit out some figures because there were too much. The way I controlled this was I kept all the people in groups. There are foreground groups and groups by the houses, and by clumping, I organized those clumps and made sure that those vignettes separate so that they don’t look so merging.

It is like being a director of a play; staging and positioning the figures are essential to point out the area of focus. I wanted to show a day in this city life instead of seeing through just one person’s eyes. I also told myself stories I made up about the figures while I was painting to instill a life in them. For me, being the artist is a bit scary in terms of this, because you don’t want to paint a story that doesn’t support the theme.

Q: And what was the major challenge you encountered as you were creating the scene?

Stasinos: I don’t know if I would call it the major challenge, but the first big problem I saw when I was approached to do it was when Bradford and Michael Smith showed me the original photographs of the site, I could not imagine how I could make something interesting out of them (Image 4). My first version of the illustration for addressing that I was just to use some white to give some effect of lots houses on it (below).

I addressed my hesitation of doing it from that point of view because the way I saw the original picture, at least the first when it was presented to me, it seemed not much different than a backdrop you see in a theater. I think Bradford came to the rescue. He mentioned that he wanted a market scene. It made perfect sense. I thought if I could build the market scene in the foreground with people who are like the actors activating the scene, it could become very interesting.

So then I got more information on where there had been more houses or where had been additional buildings. I went from a rural scene to making it a housing development. I didn’t realize until later, when I was working on the painting during my sabbatical, that the site had a high density of people living there at the time, maybe around 5,000 people.

With that many people looking different from one another and wearing different clothes and hairstyles in one painting, that was the biggest challenge, which was conceiving it.

Andrews: Michael has never seen the actual site. A lot of people think that artists work only with their imaginations, but that is not always true. Because of his unfamiliarity with the site, I appreciated him because he did ask incisive questions and wanted feedback. He worked very hard to be as accurate as he possibly could. I know that there are other artists who would not be so worried or concerned about accuracy, and that’s one of the things that I think makes his reconstructions so valuable.

Everybody loves the illustration. The details really brought the city to life, and that’s exactly what we wanted.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

To learn more about The Calixtlahuaca Archaeological Project and the city of Calixtlahuaca, please visit the official website.

Bradford Andrews has written blogs about this anthropology and art collaboration.