How tough do you have to be to forge a new path?

Colleen Hacker

Colleen Hacker was on top of the world when she came to PLU. At age 22, she’d already been invited to two Olympic trials in two different sports, and had played in five national championships. She found herself teaching and coaching at a somewhat random, D-3 school she’d never even heard of because it was the only institution that would offer her a chance to both teach and be the head coach. Against the advice of some of her mentors, she took the position.

While Colleen certainly wasn’t out of her depth athletically or as a coach, she was entering into an environment with a “very homogenous, heterosexual, white male, male-dominant status quo… It wasn’t just the norm, you know, it wasn’t 60/40, it was 98/2.”

“If I listened to one more person stand at the podium and thank their wife who made this all possible…” She rolled her eyes. “That was the role of women.”

Colleen had four athletes on her first intercollegiate team who were older than she was. She found it difficult to secure the professional respect she felt she deserved, and to juggle the workload (she had to teach five classes, compared to the football coach’s one), let alone try to “rock the boat” and challenge the institution.

This came to a head early on: in her second year of coaching (in the early 1980’s), Colleen’s (women’s) field hockey team qualified for nationals, for the first time in PLU history. So did the (men’s) football team. Citing budget constraints, the administration opted to only send the football team.

Colleen was incensed, and Sharon Taylor, one of her mentors and a Title IX expert, urged her to “take their asses to court.” But she wasn’t interested in taking legal action at the time. PLU ended up dropping the sport the very next year.

Reflecting on her career, Colleen does regret not being more involved in the legal fight against the sexism she and her athletes were facing.

Reflecting on her career, Colleen does regret not being more involved in the legal fight against the sexism she and her athletes were facing.

“They benefited from my fear. And they benefited from my age,” she said simply.

But the flip side is how proud she is of the team climate she created, and her conscious efforts to prioritize inclusivity on her teams, even when this was discouraged by the institution or by community parents. She glowed as she recounted stories of athletes’ parents going over her head to complain to her boss about the inclusive environment she created:

How I handled team climate? I’m just telling you, it’s a 10. I’m super proud.

The broader sports world would have to agree, and Colleen has consistently been lauded for her expertise in the field of sports psychology. She has been on the coaching staff for the Olympic games five times over, and worked with the US National Women’s Soccer team, in addition to other national teams. At PLU, she was also instrumental in the founding of the women’s studies department, and continued to advocate for gender parity in academics and athletics.

But PLU in the 1980s, according to Colleen, was a hard environment to break into. She hasn’t made it this far in her career without significant regrets about what she felt was possible to do and say.

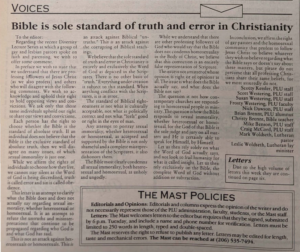

A 1996 letter-to-the-editor from other members of the Athletics Department responds to (and agrees with) an editorial from Lindsay Tomac, in which she fervently opposes student groups dedicated to queer activism at PLU.

“It was an era, in ’79, ’80, and ’80s, where you knew what was right, but if you spoke up, you could be right and out of a job,” she explained. “Those are your two options. You can shut up and work, or you can speak up and you can win in the court, but you’re going to be unemployed and unemployable.”

Campus culture, said Colleen, also made it difficult to discuss sexuality and queerness during the era in which she entered PLU. She spoke about the divide between upper and lower campus (lower campus being where athletics are typically seated, and where student athletes typically live), and the chilling effect of the conservatism there. This was only reinforced by the 1996 letter published in The Mast by key athletics staff, including football coach Frosty Westering, that championed the Bible as the “sole standard” for Christianity and morality. It was a transparently anti-queer op ed.

All this together meant that the theme on campus was “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Acknowledge, and Don’t Discuss,” said Colleen. “You break any of those rules, and the hammer is going to come down. Don’t get me wrong, not from everybody. But it’s going to come down in a public and personal and professional way, and it’s going to be explicit. You’re not going to just get the sense that you’re ostracized, you’re not going to just get the sense that you are other; you’re going to be called into the office and [they will] say ‘this is not how we do things around here.’”

In our interview, Colleen frequently spoke about the need to see “humanity” in its purest form and escape the Parkland bubble–she used to drive up to Pike Place Market in Seattle just to people-watch. Since departing her coaching position at PLU, she’s gotten the chance to maintain her national sphere of influence and involve herself in different opportunities beyond this bubble. She still teaches on campus, because she enjoys it. (After all, the chance to teach was what brought her to PLU in the first place.)